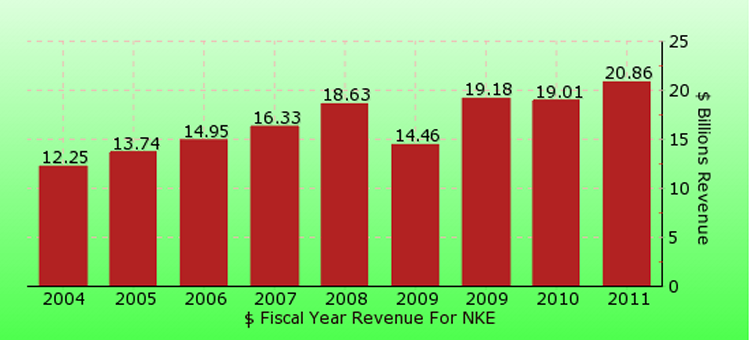

Nike Revenue, Updated

Korzeniewicz notes that Nike's revenue grew from $270 million in 1980 to $3 billion in 1991. As the chart below demonstrates, the company's explosive growth has continued in recent years.

The twin keys to Nike's success

The keys of Nike's success, continued

Korzeniewicz attributes Nike's extraordinary success to "its twin strategies of overseas subcontracting and domestic marketing" (168).

The two strategies are related, he notes, and should be understood as the company's successful effort to manage the entire chain that links raw materials in the ground (like petroleum) to products in the hands of consumers:

“Nike's successful implementation of its overseas sourcing strategy can best be understood as part of the firm's effort to retain control over highly profitable nodes in the athletic footwear commodity chain, while avoiding the rigidity and pressures that characterize the more competitive nodes of the chain” (163).

“Nike's successful implementation of its overseas sourcing strategy can best be understood as part of the firm's effort to retain control over highly profitable nodes in the athletic footwear commodity chain, while avoiding the rigidity and pressures that characterize the more competitive nodes of the chain” (163).

What is a Commodity Chain?

The graphic on the following slide illustrates a very simple chain tracing the path of a single part (the keyboard) from a very complex product that includes hundreds of such parts. Like Nike, today laptop manufacturers gain competitive advantage by forming alliances with dozens of different businesses and managing those relationships.

Commodity Chains 2

.png/1024px-Supply_and_demand_network_(en).png)

Manufacturing: First-stage Globalization

Nike avoids competing with companies in manufacturing, where the competition is fierce and the profit margins are tiny. Instead, it has turned itself into a customer of shoe manufacturers.

Nike contracts with hundreds of manufacturing companies in dozens of countries, and it constantly matches its needs (e.g. lowest cost vs. more skilled workers and sophisticated assembly lines) to particular countries and manufacturing firms.

Nike contracts with hundreds of manufacturing companies in dozens of countries, and it constantly matches its needs (e.g. lowest cost vs. more skilled workers and sophisticated assembly lines) to particular countries and manufacturing firms.

Most importantly: because Nike does not own any of these factories or machinery, it can move on when a better deal presents itself.

First-stage Globalization: Divisions in the World Economy

To explain Nike's approach to manufacturing, Korzeniewicz cites a common distinction drawn from World Systems Theory, which divides the sectors within the world economy into Core, Semi-periphery, and Periphery

- Core

- These are the most developed nations or regions, like the United States, Western Europe, Japan, etc. Most of the goods still manufactured in these regions are high-technology products like airplanes and electronics.

First-stage Globalization: Divisions in the World Economy, continued

- Semi-periphery

- These are industrializing economies and manufacturing centers with characteristics of both the core and the periphery. They are places like Mexico, Poland, and Iran, with workforces, infrastructure, and businesses capable of building more sophisticated products than those made in the periphery. Labor costs are correspondingly higher as well, though not as high as in the core. Korzeniewicz cites both South Korea and Taiwan as semi-periphery.

First-stage Globalization: Divisions in the World Economy, continued

- Periphery

- These are some of the least developed regions in the world, for example Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Nigeria. Low-cost labor is their major competitive advantage in the world economy. Korzeniewicz cites China, Indonesia, and Thailand.

In the years since Korzeniewicz published this article, however, things have changed. While many Americans believe that China offers companies only low-cost labor, in fact it now manufactures many sophisticated products that simply can't be made in the United States. A 2012 New York Times article on the Apple iPhone offers a case in point.

Markets and Marketing as Nodes in the GCC

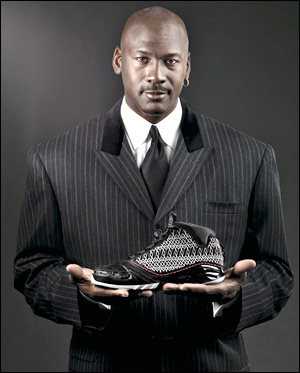

Of course, Nike's success stems from more than just its creative management of globalized manufacturing. Rather than shoes, Nike's main "product" is actually in consumers' heads. Nike manufactures the feelings and ideas that we associate with the Nike swoosh.

We wear Nikes in order to associate ourselves with those feelings and ideas, not because they allow us to play a better game of <fill in the blank>.

As Korzeniewicz notes, the athletic shoe companies managed to create a new market for their products: the vast majority of "athletic" shoes purchased today are not used for athletics (162). Instead, they are bought by young people as everyday wear.

Beyond Korzeniewicz : Markets and Second-stage Globalization

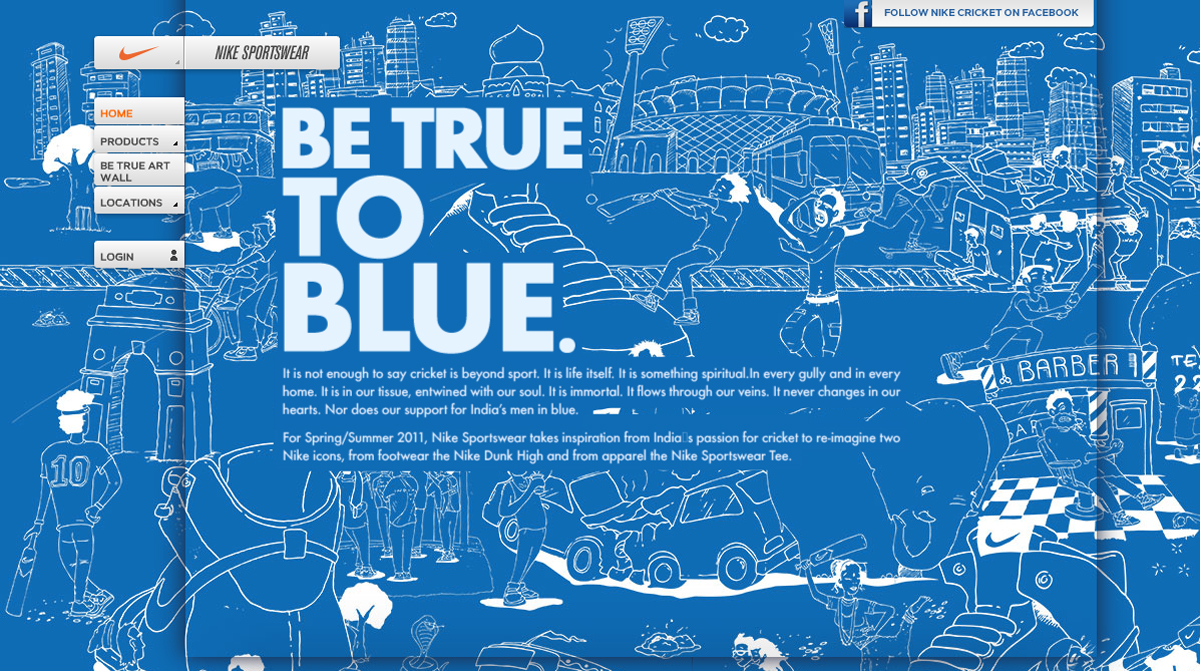

In recent years, Nike has continued to create new markets through similar means: the difference is that increasingly these consumers are not Americans.

Although Korzeniewicz's 1994 article does not address this trend, it is a key aspect of economic globalization in the two decades since it was published.

Another answer to "Why U.S. Companies aren't so American anymore"

"An apocryphal tale is told about Henry Ford II showing Walter Reuther, the veteran leader of the United Automobile Workers, around a newly automated car plant. 'Walter, how are you going to get those robots to pay your union dues,' gibed the boss of Ford Motor Company. Without skipping a beat, Reuther replied, 'Henry, how are you going to get them to buy your cars?'"

Printed in The Economist, this anecdote from the 1950s underscores a key difference between U.S. companies (like Ford) then and transnational companies (like Ford) today. It's increasingly less important to many companies whether or not Americans can buy their products.

Nike Ad Campaign: Bleed Blue (2011)

www.nikecricket.in: "Be True to Blue" (2011)

"Cricket in Town" (2007) feat. Zaheer Khan and S. Sreesanth

"Parallel Journeys" (2012)

Summary Questions (214)

- What is a global "commodity chain"?

- What does the rise of such chains in many sectors reveal about the division of labor around the globe?

- Who benefits most from the work done in such chains?

- What general lessons can you draw from Korzeniewicz's case study about the Nike corporation?